London strikes an interesting accord between the old and the new. This balance is visible on the city's skyline as St. Paul's dome appears next to the new, sharp facade of the Shard or from the Thames when you compare the Tower bridge with the sleek lines of the Millennium bridge. Historic landmarks back up into modern office buildings, English kings lie under car parks, and theatres sink back down into the marsh and face oblivion beneath corporate headquarters.

One old part of London that is trying to push back against the rapid movement into the future is the Rose Theatre on Bankside. While the Rose was the first theatre built on Bankside, its legacy has been dwarfed by its close neighbor, the Globe. The Rose, having never received a champion like the man responsible for rebuilding the Globe, Sam Wanamaker, was built over and the theatre's foundations slowly sank back down into the marshy soil.

|

The archeological site at the Rose.

Source: http://www.londontown.com/

NearByHotels/Hotels/33871/Directory/

Hotels-near-Rose+Theatre/ |

But that isn't all the Rose wrote. While the theatre may not have had the same kind of champion as the Globe, it certainly had its own staunch supporters. Archaeologists from the Museum of London uncovered two thirds of the theatre's ground plan in a dig in May 1989, but city infrastructure prevented them from finishing the dig. Soon after, the Rose Theatre Trust was formed to prevent the construction of a new building on the site that would destroy the theatre's remains. Actors, academics, and the public at large joined the campaign to 'Save the Rose,' with the likes of Dame Judi Dench, Sir Ian McKellen, and Lord Laurence Olivier speaking in support of the theatre. Lord Olivier's final recorded message,"Cry God for Harry, England, and the Rose," was played over loud speaker at one of the campaign's rallies. The campaign succeeded, and now the Rose is putting on productions and opening the site up to the public in the hopes that they can raise awareness about the theatre and its history and fund the completion of the dig and the reconstruction of the theatrical space.

|

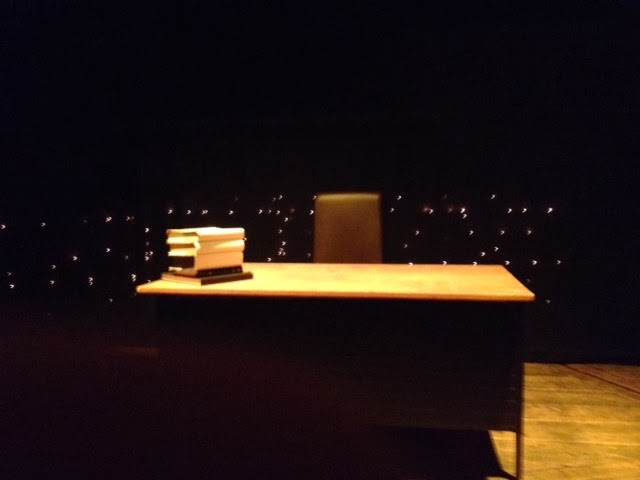

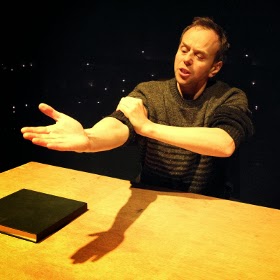

Christopher Staines as Faustus.

Source: http://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/

reviews/02-2014/doctor-faustus-rose-theatre

-bankside_33438.html |

The productions in the Rose emphasize the meeting of past and present that often occurs in London theatre. On Friday evening, I attended the theatre's production of Christopher Marlowe's

Doctor Faustus. To celebrate Marlowe's 450th birthday this month, the Rose brought

Faustus back to the place it first appeared 420 years ago. Modernizing the production, the number of actors was reduced to one, Christopher Staines, who played Faustus and a host of other internal characters brilliantly. While this reduction of actors certainly required some scenes to be cut, the use of a loud speaker recording for Mephistopheles (perhaps harkening back to Lord Olivier's loud speaker announcement that helped save the Rose) and interaction with the audience kept the play from feeling starkly populated. Staines treats Marlowe's language almost reverentially in the first half of the play and the last scene of Faustus facing Hell, which made the break in language during Faustus's romp through Rome even more engaging. As Faustus makes himself into a clown as he tricks the Pope, puts antlers on a knight, and fetches grapes like a servant, Staines takes liberties with the language that make the disparity between what Faustus wants (to rule the world) and what Faustus actually does especially tragic.

|

| Faustus's study, surrounded by candlelight |

Faustus certainly seems grand as Staines runs out through the archeological sight, splashing through the water that perpetually stands in site, jumping off ledges, climbing up walls, and standing in the exact spot that Faustus's original portrayer would have stood. But as he pleads with Mephistopheles and with himself, the audience watches that grandeur slip away until he is left sitting in a chair contemplating damnation. The production internalizes Faustus's struggle, abandoning Marlowe's physical demons to emphasize Faustus's mental ones. This choice makes

Doctor Faustus into a modern psychological drama, bringing Marlowe's play into the present while physically maintaining its ties to the past in the Rose.

When past and present collide, room is created for monumental change. When someone is willing to challenge the established order, like Christopher Marlowe's challenge to Christianity in

Doctor Faustus or Charles Darwin's challenge to existing scientific ideas, society faces a choice: to accept or reject that challenge. When the challenge is accepted, ideas change, new discoveries are made, and society's fabric is essentially altered. And these earlier challenges set up the precedent for further challenges. Thus, because Kit Marlowe did something that had never been done before and actually evoked demons on the stage, space was created within the theatre and within Marlowe's own work for further experiments to occur, including Staines' one-man race through Faustus's mind. Staines remarks at one point that Marlowe is probably rolling in his grave at the changes he made to the play, but I think Marlowe would have appreciated the risks Staines took. After all, an innovator will always appreciate a fellow innovator. And it is such innovation, in theatre, science, art, literature, music, and life in general, that allows us to moving into the future, while respecting and preserving the past.

London strikes an interesting accord between the old and the new. This balance is visible on the city's skyline as St. Paul's dome appears next to the new, sharp facade of the Shard or from the Thames when you compare the Tower bridge with the sleek lines of the Millennium bridge. Historic landmarks back up into modern office buildings, English kings lie under car parks, and theatres sink back down into the marsh and face oblivion beneath corporate headquarters.

London strikes an interesting accord between the old and the new. This balance is visible on the city's skyline as St. Paul's dome appears next to the new, sharp facade of the Shard or from the Thames when you compare the Tower bridge with the sleek lines of the Millennium bridge. Historic landmarks back up into modern office buildings, English kings lie under car parks, and theatres sink back down into the marsh and face oblivion beneath corporate headquarters.

No comments:

Post a Comment